In this section, I will attempt, with the risk of sounding amateurish, to ambitiously synthesize Carlo Rovelli’s phenomenal little book, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics into the preceding idea of incarnation and of being interconnected. Some portions of the book read more like poetry than a science book. First, I see God as the author and perfecter of unitive consciousness, the foundation of all connectedness. Secondly, Rovelli claims, “The very foundation of science is to keep the door open to doubt.” This statement gives me confidence and respect.

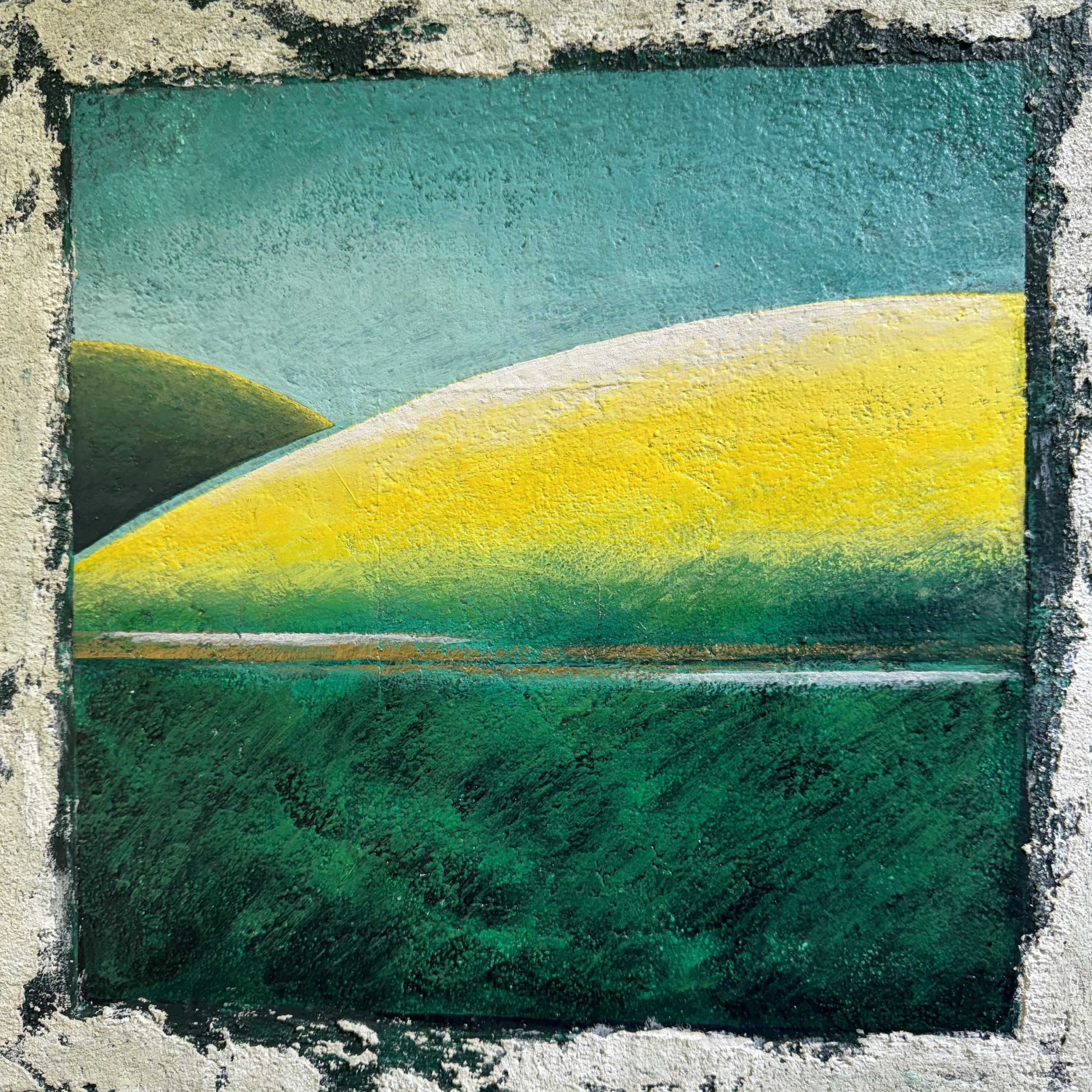

Quantum mechanics and experiments with particles have taught us that the world is a continuous, restless swarming of things, a continuous coming to light and disappearance of ephemeral entities. A set of vibrations, as in the switched-on hippie world of the 1960s. A world of happenings, not of things. [1]

A tree is not a thing, as is a rock, it is a happening. From a close to 14 billion years perspective, nothing can be seen as a thing, but a happening.

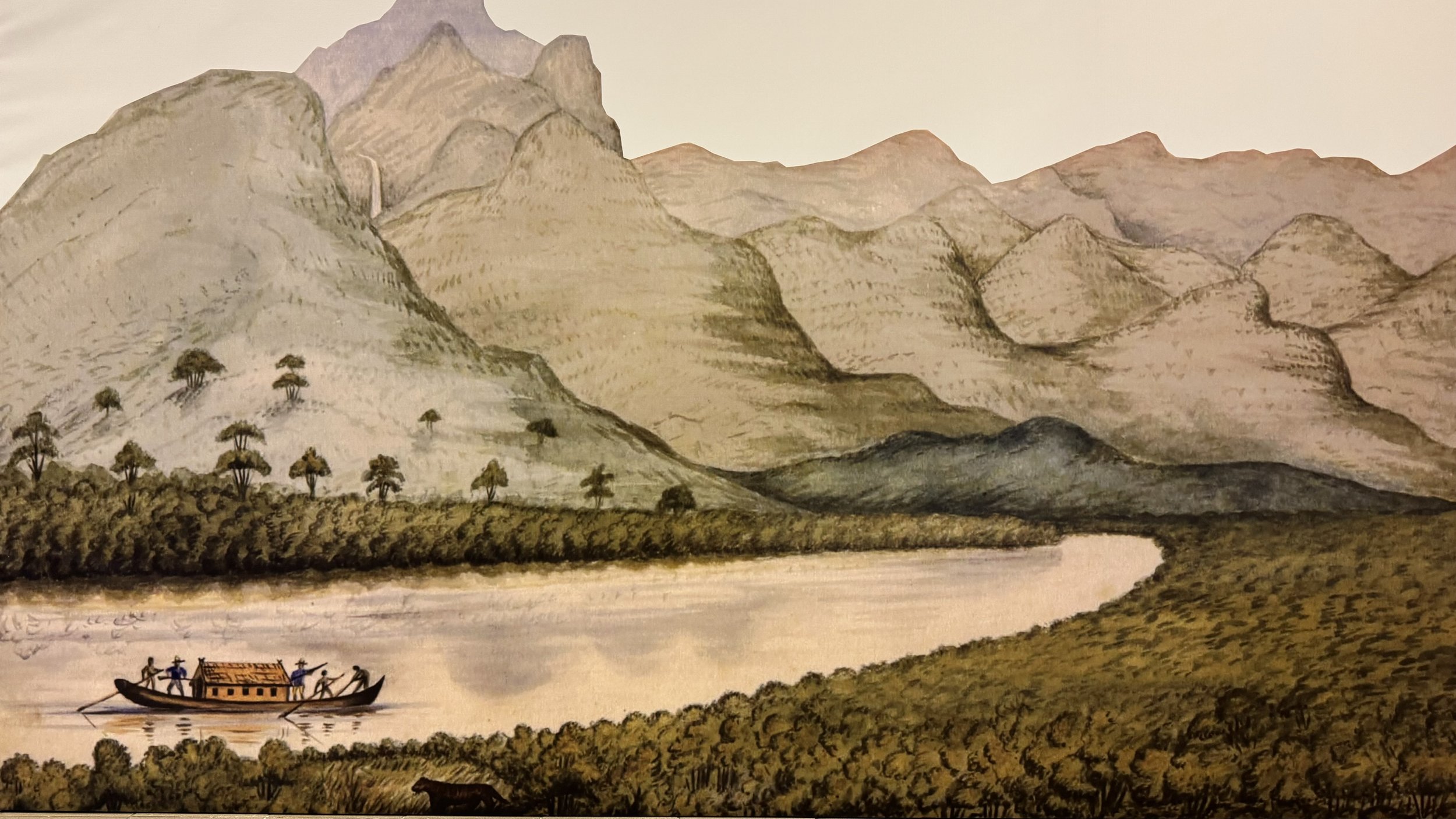

We are made up of the same atoms and the same light signals as are exchanged between pine trees in the mountains and stars in the galaxies.[2]

We are made of the same stardust of which all things are made, and when we are immersed in suffering or when we are experiencing intense joy we are being nothing other than what we can’t help but be: a part of our world.[3]

I find the above claim simply breathtaking and mind-numbing. Incarnation relates to quantum mechanics theory as all things are connected. How they are connected and how they interact remains a profound mystery. As humble subjects, we recognize God as the origin and designer of all incarnations. Listen to Rovelli below.

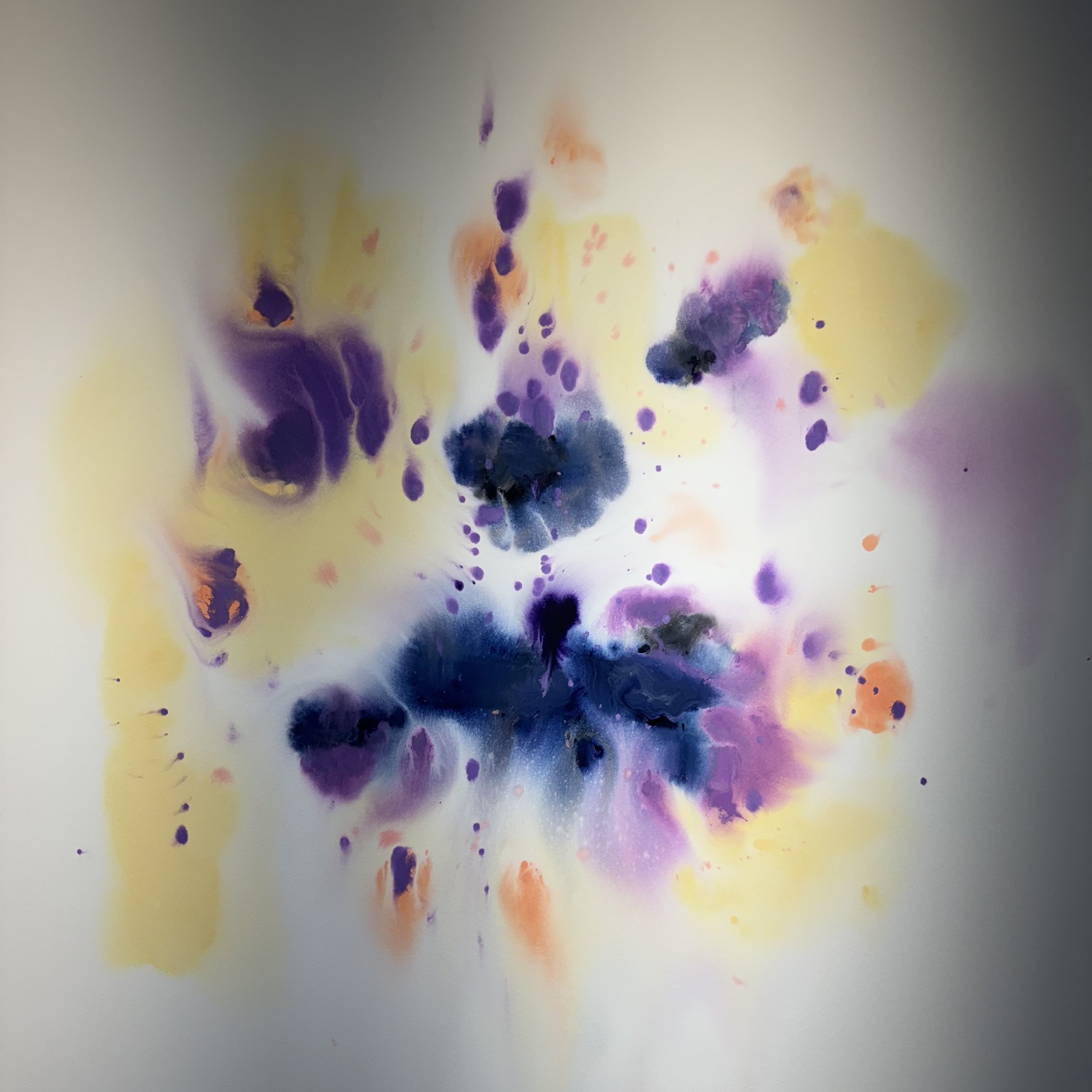

I believe that this example demonstrates how great science and great poetry are both visionary, and may even arrive at the same intuitions. Our culture is foolish to keep science and poetry separated: they are two tools to open our eyes to the complexity and beauty of the world.[4]

I was not prepared to read the above statements. What it reminded me of was a section I read recently from Mary Oliver’s[5] Upstream.

I would say that there exist a thousand unbreakable links between each of us and everything else, and that our dignity and our chances are one. The farthest star and the mud at our feet are a family; and there is no decency or sense in honoring one thing, or a few things, and then closing the list. The pine tree, the leopard, the Platte River, and ourselves—we are at risk together, or we are on our way to a sustainable world together. We are each other’s destiny.[6]

Rovelli and Oliver, as scientists and poets, have attempted to describe reality utilizing their trained intuitive lens and finite human language. Additionally, they know not to or dare to “close the list.” Beware of ourselves or anyone else for that matter in being the authority of choosing the list. From my personal, subjective, and experiential lens[7], my intuition concurs with that of Oliver’s and Rovelli’s and my soul knows the vision of a “sustainable world together” to be true. Before leaving this section, I must include Rovelli’s “conclusion” in his book, “It is part of our nature to love and to be honest.”[8]

It is worth bringing Ilia Delio, who has been mentioned earlier, as a Franciscan sister, theologian, and scientist (and an expert on Pierre Teilhard de Chardin), to validate the above assertion.

Christ invests himself organically within all creation, immersing himself in things, in the heart of matter, and thus unifying the world. The universe is physically impregnated to the very core of its matter by the influence of his superhuman nature. Everything is physically “christified,” gathered up by the incarnate Word as nourishment that assimilates, transforms, and divinizes.[9]

Richard Rohr was the first one who enlightened me with the differentiated concepts of pantheism and panentheism. Pantheism is defined as “God is everything.” Panentheism says, “God is in everything.” God is the least common denominator in the entire universe. Suddenly God being at the center, there is mysterious “Christified” order within disorder, unknown (and perhaps unknowable) certainty within uncertainty. I would like to close this paper with the idea of “unifying the world.”

[1] Carlo Rovelli, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, Penguin Books, 2014, 32-33.

[2] Ibid, 64.

[3] Ibid, 77-78.

[4] Carlo Rovelli, Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity, New York: Penguin Press, 2014, 88.

[5] Oliver, lover of nature, was an American poet who won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

[6] Mary Oliver, Upstream: Select Essays, New York: Penguin Press, 2016, 154

[7] This phrase is based on my 2023 ASFM paper titled Human and Spiritual Journey as Subjective, Personal, and Experiential.

[8] Carlo Rovelli, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, Penguin Books, 2014, 78.

[9] Ilia Delio, The Unbearable Wholeness of Being: God, Evolution, and the Power of Love, Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books: 2013, 79.